- Islington as a Place of Refuge – Tour Stop 3

- Significance: Location of Swiss-Italian entrepreneur Gatti’s ice well

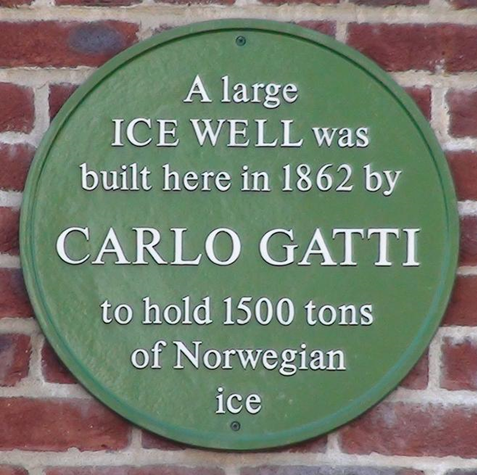

Italians have been settling in London for centuries, with a great many settling in Islington. Carlo Gatti left his Swiss-Italian home town in 1847 to go on to become a successful entrepreneur in Islington, bringing hot chocolate and ice creams to the masses. The plaque to his ice well on Caledonian Road remains an import reminder of Gatti’s personal legacy, and of the major role Italian culture played in shaping our borough and influencing what we eat.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, Italy was subject to significant and turbulent changes. Dominated by the French during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Napoleon was proclaimed King of Italy in 1805. Large numbers of farmers were forced from their land as a consequence of widespread agricultural destruction following the wars. Many skilled workers were also forced to leave due to economic hardship, including barometer and precision instrument makers from Como and specialised plaster makers from Luca, who were attracted to the growing city of London. Key figures from Italian Society were exiled during this period by the new regime who also settled in London. Notable figures include the statesman and republican activist Giuseppe Mazzini (1805 – 1872), the poet and artist Gabriele Rosetti (1783 – 1854) and patriot Antonio Panizzi (1797 – 1879). Clerkenwell quickly became the centre for this new Italian community, gaining the nick-name ‘Little Italy’. The area was relatively affluent and became a hub for these skilled craftsmen. Successful firms such as Negretti & Zambra, manufacturers of thermometers, barometers and optical instruments such as telescopes, populated the area.

Italy suffered a severe economic collapse in the latter part of the nineteenth century which saw a much bigger wave of emigration to the UK. Driven by economic desperation, huge numbers left their homeland with many flooding into London’s Little Italy. Most of these newer arrivals lived in slum-like conditions and had very little to do with the earlier, economically successful settlers. Little Italy was an area that was actually quite divided. The worst slums were found around Saffron Hill and Leather Lane, an area full of pickpockets and fences, described by Charles Dickens in great detail in Oliver Twist. Surveys conducted in the 1880s showed that Italian household conditions were the worst of any group in London. The Italian consul published a report in 1895 estimating there were 12,000 Italians in London, with southern Italians traditionally making their home in Little Italy while those from farther north were establishing a newer base in Soho.

Switzerland, known as the Helvetic Confederation at the end of the eighteenth century, had also been invaded by the French during the Revolutionary Wars. Swiss independence from the French was finally established at the 1814-15 Congress of Vienna. Ticino, the country’s only Italian speaking territory, became a canton within the Helvetic Confederation in 1802. It was a particularly poor part of the country, with a localised rural-based economy. The contemporary geographer Conrad Malte-Brun described “The canton of Tesino [Ticino] is the poorest, and the people the most ignorant of any in Switzerland.” As with neighboring Italy, poverty in Switzerland led to mass emigration, especially from Ticino. The economic situation was so dire that local councils actually paid men to leave!

Carlo Gatti (1817-1878) was born in Ticino and was one of the many migrants who left in search of a better life elsewhere. He would go on to become a hugely successful entrepreneur, making a big impact both here in Islington and across the capital. He was responsible for the introduction of several ‘new’ and exciting eating experiences for Londoners, including making ice cream available for everyone! Gatti initially left for Paris in 1847, where his father was employed selling chestnuts. He walked the 600 miles from Switzerland to meet him in the French capital. Later that year, Gatti moved to London, settling in Little Italy, and started selling waffles from a stall in Greville Street.

Gatti was a talented entrepreneur, building up his business quickly. In 1849 he went into business with a fellow Swiss countryman, Battista Bolla, opening a café and restaurant in Little Italy. They specialised in selling chocolate and ice cream. Drinking chocolate was also novelty at the time and they exhibited a chocolate making machine in the window of the café to attract customers. In I851, Gatti and Bolla exhibited their chocolate making machine at the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace which was described by Queen Victoria as a very curious machine. The same year, Gatti established a stand in Hungerford Market, near Charing Cross, selling pastries and ice cream in little shells. The ices sold for one penny and he is credited with being the person who introduced ice cream to the masses, previously only a luxury the rich could afford. There are claims that he sold up to 10,000 penny ices per day by 1858. The ice cream on these ‘penny licks’ was dispensed onto small glass stems. These stems were not cleaned before being reused, an incomprehensible concept by today’s standards!

In 1851, one third of the working Italian population were travelling street musicians, with many playing the mechanical barrel organ. By 1871, this figure had substantially increased to half of the working population. The Italian community was not always popular though. There were calls from London’s middle classes to ban these musicians, who viewed them as a noisy nuisance. By 1900, selling ice cream had become the dominant trade for Italians, replaced organ grinding as most common occupation, with 900 ice cream vendors living in Little Italy. The Ice-Cream Man or ‘okey-Pokey Man was a common sight. This colloquial name came from his cry of Ecco un poco! meaning ‘Here’s a little (taste)!’ in Italian.

Gatti started importing ice from Norway around 1857. The ice was shipped to London, brought up the Thames and eventually transferred onto barges in Limehouse. The barges took the ice up the Regent’s Canal to Gatti’s two newly opened ice warehouses. One of these was located on Battlebridge Basin (and now houses the London Canal Museum) and the other on Caledonian Road, near Cally Park. Its location is marked by a green plaque.

Prior to refrigeration, the best way of storing ice was away from sunlight, underground in circular brick-lined ice wells. These wells were approximately 30 feet in diameter and 40 feet deep, therefore able to store large quantities of ice. Ice packed closely together minimises melting, and the larger the volume stored together the colder it stays. The ice was then cut and distributed across the city on his distinctive yellow and brown wagons to the ice cream makers, though the bulk was bought by merchants dealing in dairy, meat and fish products.

In 1854, a fire closed the Hungerford Market. Fortunately, and slightly unusually for the time, Gatti was insured and received financial recompense for the loss of his business. He used this money to build a music Hall in 1857, however this venture was short-lived and the building sold to the South Eastern Railway in 1862 and subsequently demolished in order to expand Charing Cross Railway Station. Using the proceeds from this sale, he opened another music hall in Westminster in 1865 and a third under the railway arches under Charing Cross Station in 1867. The Charing Cross Theatre now occupies this site. After making his fortune in London, Gatti retired to his native Switzerland in 1871.

The Italian population peaked in the early twentieth century, however slum clearance, road building and development in Clerkenwell led to the gradual dispersal of the Italian community across London. In the Second World War local Italians were viewed as enemies of the people – and sent to prison camps and the Little Italy district suffered heavily during the Blitz; However, the legacy of the Italian population remains in the area. Not only did Gatti, and scores of Italian migrants, make an impact on the London food scene by making chocolate and ice cream accessible to the masses, they also made huge contributions to the economy and left a lasting legacy on our cultural scene.

This article was produced for Islington as a Place of Refuge, an online tour developed by Islington Museum and Cally Clock Tower, in conjunction with Islington Guided Walks. Centred around Refugee Week 2020’s theme of ‘Imagine’, Islington as a Place of Refuge explores diverse stories from migrant history in relation to the London Borough of Islington.

Leave a comment