Prior to refrigeration, ice from the Regent’s Canal was integral to Islington’s businesses for food preservation, particularly to meat, fish and dairy merchants. Ice also played and important role in hospitals where it was in use to relieve inflammation. It was a difficult product to gather and store in the quantities required by Britons, thus its quality was often poor. This meant that innovation was required. The Regent’s Canal was home to developments that meant that ice could go from a scare luxury to product available to most: imports and artificial manufacture.

Trading Ice

During the 19th Century, demand for ice in London far exceeded what could be collected locally. A way of combatting this shortage was importation from countries with much colder climates. This began in the 1840’s, with ice trade commencing with America. The Wenham Lake Ice Company in Massachusetts, USA, was one of the most prominent American exporters of ice and received a royal warrant from Queen Victoria to import their product.

Andrew Wynter, in Our Social Bees; or, Pictures of Town & Country Life, and other papers, published in 1865, the mystical ice imported by the Wenham Lake Ice Company, “A very long way off, in the New World, there is a great cup, hundreds of feet deep, made in the mountains. This cup is always full of crystal water, which in the winter season gets so cold that great ships come and carry it all over the world, so that every person, when he is heated as you are, can, if he likes, have a draught of its delicious icy contents.”

In 1844, the Wenham Lake Ice Company opened a storefront in The Strand, London where they would put on display a large block of ice in the window every day. A newspaper was placed on the other side of the block of ice so that passers-by could read the print through the ice, from outside the store looking into the window. It was a truly unique site to the people of London, many of which had never had the opportunity to see proper chunks of ice before.

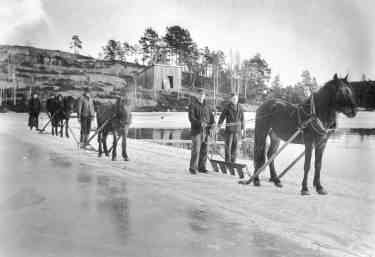

The Wenham Lake Ice Harvest destined for London

The ice harvesting season generally commenced when the ice was approximately 30cm thick on the lake. It was imperative that no recent snow had fallen and melted on the ice. A line 5-7cm deep was ruled across the surface by a small, sharp hand-plough, which served as a guide to a horse-plough called the marker. The marker cut two parallel lines, about 45cm apart, and then repeated at a right angle the frozen surface to make perfect squares. About 15cm deep after the horse-ploughing the lines were sawn off individually and floated over to be transported into the ice house via a ramp out of the water and sledge.

To get these blocks of ice to London still frozen was quiet the feat. The real reason Wenham Lake ice was so popular in England was not necessarily due to the lake being of better purity than others that also produced ice, but largely due to its location. Just 29km north-east of Boston, Wenham Lake was in close proximity to the sea, provided a shorter route to the ship it would cross the Atlantic on, and therefore maintain its frozen state better. The ice was packed as tightly as possible into a train car which could reach the port within an hour. The blocks were then packed into the hull surrounded by saw dust with every effort made to reduce contact with the salty sea air. In spite of best efforts, a third to half of the volume of ice could be lost during the journey. Wynter talks of one ship that arrive in London with just 326 tonnes of ice when it left Boston 51 days earlier with 502 tonnes of ice on board. The main reason for loss was accounted to the salt air and poor drainage meaning that saturated sawdust became a conductor of heat and exacerbated the problem.

Common use of ice in England

Any block of ice that was remotely tainted in colour, or presented any impurity, was immediately put aside as rough ice for freezing purposes. Consequently, those using Wenham Lake ice were always confident in the safety in using the product in direct contact with food and beverages.

Wynter rejoiced the proliferation of ice houses from the mid-19th Century, with a new portable refrigeration method developed by the Wenham Lake Ice Company that meant ice was no longer a luxury for the rich, but one that could be shared by anybody with £10 a year to spare: “Henceforth, no decent householder need tolerate swimming butter or lukewarm drinking water in the dog-days. Neither should tough joints, warm from the slaughter-house, be suffered to pass as heretofore, on the plea that “there is no keeping meat this hot weather.” We have invented a shield that the arrows of Apollo cannot penetrate, and the iced larder will, without doubt, soon become as much a universal comfort among us as the bright fireside.”

A Swiss Italian in Islington

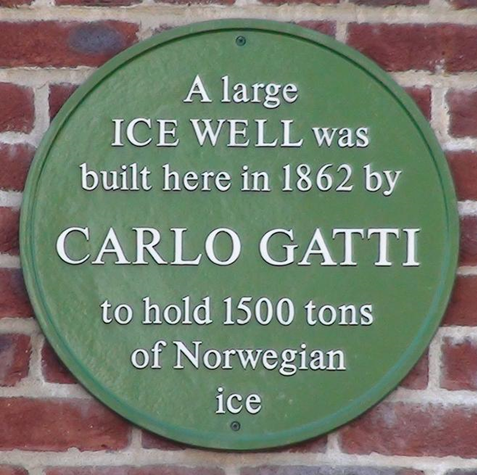

Carlo Gatti (1817-1878) was born in Ticino, Switzerland. He was one of the many migrants who left in search of a better life elsewhere during a period of extreme hardship. He would go on to become a hugely successful entrepreneur, making a big impact both here in Islington and across the capital.

In 1847, Gatti moved to London, settling in Little Italy, and started selling waffles from a stall in Greville Street. In 1849 he went into business with a fellow Swiss countryman, Battista Bolla, opening a café and restaurant in Little Italy specialising in chocolate and ice cream. The same year, Gatti established a stand in Hungerford Market, near Charing Cross, selling pastries and ice cream in little shells. The ices sold for one penny, gaining them the nickname ‘penny licks’. The cost of these penny licks allowed the masses to enjoy ice cream, a luxury that was previously only afforded by the wealthy. There are claims that he sold up to 10,000 penny ices per day by 1858.

The Regent’s Canal was integral to Gatti’s ice cream business, but he also to other local businesses that he supplied ice to. As the local demand for ice grew, there was a pressing need to find additional supply of ice. Carlo Gatti’s solution was not to jump aboard the America ice trade, but to look to Norway.

Norwegian Ice and Gatti’s Ice Wells

Gatti began importing ice from Norway in 1857, with 400 tonnes of imported Norwegian natural ice brought to Islington in that first year. The ice was shipped to London via the Thames and transferred onto barges in Limehouse. The barges took the ice up the Regent’s Canal to Gatti’s ice warehouses. One of these warehouses was located on Battlebridge Basin, the first well established in 1857 and the second in 1863, and there was another ice warehouse on Caledonian Road established in 1862.

Prior to refrigeration, the best way of storing ice was away from sunlight, underground in circular brick-lined ice wells. These wells were approximately 9 metres in diameter and 12 metres deep, therefore able to store vast amounts of ice. To minimises melting, the ice was packed closely together, just as on the transport ships; The larger the volume of ice stored together the colder it stays. The ice could remain for many months, losing only about a quarter of its weight between Norway and the customer in London. The ice would periodically be cut and distributed across the city on Gatti’s distinctive yellow and brown wagons to ice cream makers, though the bulk was bought by merchants.

By 1900, as a direct result of having far more ice available locally, selling ice cream had become the dominant trade for Italians in London. With some 900 ice cream vendors living in Little Italy, the Ice-Cream Man or ‘okey-Pokey Man was a common sight. This colloquial name came from the cry of Ecco un poco! meaning ‘Here’s a little (taste)!’ in Italian.

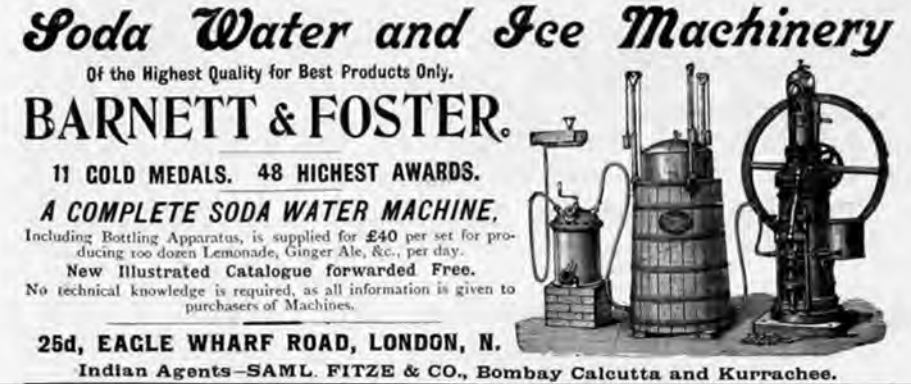

Artificial Ice

By the end of the 19th Century, artificial ice manufacturing was taking off. In the Islington area of Regent’s Canal, Barnett and Foster, as well as G.J. Worssam in Wenlock Road, manufactured ice making and brewing equipment. With the rapid advance of technology in the Victorian Era, these businesses and many more would begin replacing the natural ice trade that was the backbone of businesses like Gatti’s with widespread availability of artificial ice made locally.

Carlo Gatti’s ice wells remained in use until 1904. The natural ice trade declined swiftly and Gatti’s company converted the building into a horse and cart depot, installing new floors and making extensive alterations. The company United Carlo Gatti and Stephenson used the building until 1926, after which it was used by a number of different occupiers for warehousing and light engineering.

The London Canal Museum has occupied the site from 1992. Carlo Gatti’s original ice wells in Battlebridge Basin are understood to be the only such wells to have survived in London. With other wells throughout Britain and Europe buried and inaccessible, these are also the only known ice wells available to visit in Europe.

Article from Barging Through Islington: 200 Years of the Regent’s Canal, an exhibition exploring the two century history of the Regent’s Canal.

With thanks to Carolyn Clarke and London Canal Museum. All images courtesy of Islington Local History Centre unless otherwise stated.

Leave a comment