THE “BLITZ” PERIOD – SEPTEMBER TO JULY 1941

By W. Eric Adams (Islington Town Clerk and ARP Controller)

The 80th anniversary of the start of the London Blitz (7 September 1940 – 10/11 May 1941), during the Second World War, is being remembered nationally from Monday 7 September 2020.

This contemporary account of the Blitz period in Islington was taken from:

Adams. W. Eric. Civil Defence in Islington 1938 – 1945: an account of passive defence and certain aspects of the war as it affected the borough. October 1946

The Blitz Period

When the attack started on Islington it was very intensive, in fact the first two months were never again equalled in the number of incidents to which the [Air Raid Precaution / Heavy Rescue] Service was called. Fortunately, however, some of the bombs were of small calibre and operations were often concluded after only a few hours work.

The movement of parties was directed from the Report and Control Centre by the Controller or his representative on duty. The number of parties likely to be required to deal with an incident was estimated from details give on the air raid damage report received from the Warden and these were dispatched by telephone message to the depot most conveniently situated in relation to the incident. Reinforcements, if required, were obtained by the Party Leader of Clerk of Works by message to control through the nearest Wardens’ Post. On the completion of work the Party Leader reported the fact to Control when he would be either directed back to his depot or to another incident.

Annette Crescent

Of the more serious incidents the first to fully extend the Service was a direct hit on a trench shelter in Annette Crescent, and it is no reflection upon the men that although the operation was successfully accomplished, the unpleasant task to which they were so far unaccustomed affected them considerably for some few days after. With raiding every night, however, and the necessary shoring work next day, the parties soon got into their stride and continued to successfully answer all calls made upon them, including at times moving as reinforcements to other Boroughs. Their task was a strenuous one and so far as work permitted parties were rested for short periods during daylight hours in readiness for the inevitable stand-to when darkness fell – in fact, it was 24 hours service in the full sense of the term.

Gallantry

Typical of the work during these early days were rescue operations at Petherton Road* and Bryan Street**, at both of which Rescue personnel received awards for gallantry. At Petherton Road, where a large calibre bomb had demolished a five-storey building, a tunnel 5 feet horizontally was cut into the debris to release two casualties. The whole operation took seven hours to complete and was performed whilst the raid was still in progress, in the presence of coal gas and in wreckage which was in imminent danger of collapse. The Party Leader in charge of the work was awarded the George Medal and three of his colleagues were commended.

[*The awards for gallantry were made after the incident in Petherton Road on the night of 15/16 September 1940 all relating to members of the Heavy Rescue Service: Frederick A. Bashom (George Medal), J. Williams, C.D. Southam, A.H. Thomas (all three received Commendations)]

At Bryan Street, off Carnegie Street/Caledonian Road, on the night of 21/22 September 1940, two boys were trapped in the basement of a demolished house and a tunnel 12 feet long was required to reach them. It was formed about 2 feet square by men working in succession lying prone, throwing back the debris and fixing struts and bearers (converted from the debris) as they advanced – a risky operation cleverly performed. After 3 hours the boys were safely released uninjured over men lying flat in the tunnel and passing the boys hand over hand. For this operation two members of the personnel were awarded the British Empire Medal and a third commended.

[**The awards for gallantry were made after the incident in Bryan Street on the night of 21/22 September 1940 all relating to members of the Heavy Rescue Service: George Turner and Frederick B. McQuillan (British Empire Medals) and C E Hollis (Commendation)]

Night raids

To fully appreciate the fine work the Service was doing during this period it must be remembered that raiding invariably continued throughout the night which necessitated the men working with the minimum of light. The operation, therefore, of entering badly damaged buildings and tunnelling into masses of debris was necessarily coupled with an even greater element of risk than would otherwise have existed.

Mid-September heralded the advent of a very serious complication in the shape of parachute mines. The first in Islington – dropped at Poole’s Park – fortunately failed to explode and was successfully defused, by a Naval Officer. To allow of its removal, the Rescue Service was called upon to demolish certain garden walls and to erect a covering of corrugated iron to protect it from incendiary bombs pending removal. The local ‘Spitfire Fund’* collectors, however, saw in this a heaven-sent opportunity to raise their total, so promptly remove the covering and charged a penny a time to view the unusual exhibit. When at night this was discovered, the Rescue Service was called out once more to replace the covering.

* [Learn more about Islington’s Spitfire Fund]

A few days later, two other mines fell which failed to explode on landing, one in Wright Road, the other in Leigh Road. Both exploded while being worked upon by the naval Party. The first unfortunately killed the naval Officer, who was attempting to defuse it. This was the only casualty as the area had been evacuated.

On the night of September 26/27th however, there were two further mines, one at Camden Road and the other at Cornwallis Road and in both cases they exploded on impact with the result that the Service was fully extended. During the month the Service attended at some 130 incidents and was responsible for rescuing 100 persons alive and recovering 81 dead.

College Cross

At an incident at College Cross in October*, the Service did good work and showed great devotion to duty. The night was very dark and it was raining heavily; in addition there was a delayed action bomb of unknown calibre only 70 feet away. Parties worked through the night until exhausted but returned after a short break and insisted on working until 11 a.m., two hours after the change of shift. After consideration it was deemed inadvisable to expose parties to the danger of the adjacent delayed action bomb and volunteers were called from whom 12 were selected. Unfortunately the trapped persons were dead when recovered.

*[One of those who died in the College Cross attack, on 9 October 1940, was 96-year-old Emma Henesey of 42 College Cross. Emily was Islington’s oldest casualty on the Home Front during the Second World War]

Isledon Road and Market Road Gardens

At Isledon Road, rescue work was proceeding at an incident which had occurred on the previous night when a second high explosive bomb fell in the near vicinity killing one Rescue man and injuring four. In spite of the physical and mental shock to the men, work continued with very little interruption.

An incident which might have proved disastrous but for prompt and gallant action occurred on 15 October. Two high explosive bombs fell adjacent to trench shelters in Market Road Gardens blocking both the normal exits. The Leaders of the two parties called to the incident entered the shelter by means of the emergency escape hatches and found that an overpowering atmosphere – which was later found to be the result of carbon monoxide due to the explosion – had rendered most of the occupants practically helpless. All escape hatches were immediately opened and the work of raising the shelterers from the floor some feet below through the escape hatches by means of rope with “chair” knots was commenced. Several of the Rescue men were overcome and had themselves to be rescued before they continued after treatment. When the last visible shelterer had been removed, in all approximately 100, it was found that two were still missing. These were eventually recovered after two days buried under debris from the bomb explosion. To add to this excitement on the night of this incident, a parachute mine exploded in Caledonian Market 150 yards away.

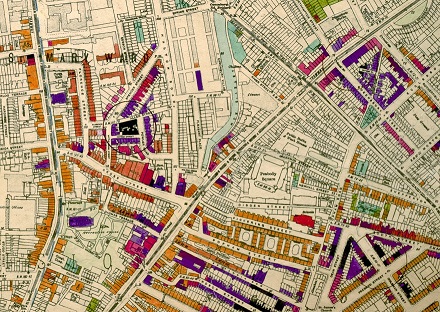

War Debris Clearance Scheme

Two other mines fell on the same night at Queen Margaret’s Grove and Britannia Row. During the month, the Service attended at 131 incidents, the most in one night being 32. 206 persons were recovered alive and 83 dead. By this time the Borough was showing marked signs of its ordeal and it was in October that the War Debris Clearance Scheme under the direction of Sir Warren Fisher was instituted, and work commenced in Islington on several of the most badly damaged areas. The Rescue Service was called upon to attend fewer incidents in November but amongst these were Radford House (London County Council housing estate) and 26 Highbury Grove an R.A.F. billet, both of which were of a serious character.

Under the influence

Another incident in November occurred in Huntingdon Street where four members of the Rescue personnel earned British Empire Medals for gallantry. A heavy high explosive bomb had demolished three 4-storey buildings and to reach the trapped persons a tunnel had to be formed through the debris, 20 feet long, which filled with a heavy concentration of escaping coal gas. The four men, working in pairs, took turns in the tunnel but all were at some stage of the work overcome and had themselves to be assisted out. The operation was successfully accomplished but three of the Rescue men had to be taken to Hospital for treatment. The effect of the gas they had inhaled badly affected their gait with the ironic result that a report was received suggesting that the men had been under the influence of drink. Remote breathing apparatus was devised later to cope with such cases as this.

“There’ll always be an England”

Whilst generally the rescue workers were directed to trapped persons by their cries of help, or in bad cases from information of their possible location given by Wardens and neighbours, it is worthy of note that on one occasion in Petherton Road a definite clue to the position of a trapped man was provided by his lusty rendering of “There’ll always be an England”. Such spirit typified the defiance of the public at that time as did the Union Jacks which were invariably planted on the highest point of the ruins. The Rescue men unofficially adopted the Union Jack as their standard and there were few lorries which did not prominently display a good specimen of the National flag.

December 1940 and January 1941 were quieter months, the Rescue Service being called upon to attend at only 14 incidents, whilst in February their services were not required at all for rescue work. It was during this period that the enemy changed to incendiary raids.

The Thatched House

In March, 12 incidents were attended, including the serious parachute mine incident in Kelvin Road where in the course of four days the Service rescued 15 persons alive and recovered 19 dead. The amount of debris created at parachute mine incidents necessitated revised technique and it was here that the principle of removing debris completely away from the scene was first introduced. A fleet of lorries was acquired and members of the Pioneer Corps worked in conjunction with the Rescue Service in removing the debris to a temporary dump in Petherton Road.

Other serious incidents during the month were direct hits on the “Thatched House” Public House in Essex and the Police Station in Hornsey Road. At the “Thatched House” where the bomb penetrated the building to explode in the bar, the Service rescued six persons alive and recovered 17 dead, whilst at Hornsey Road Police Station two were rescued alive and 10 recovered dead.

Serious incidents

Islington enjoyed a comparative lull in the early part of April, but on the night of 16th/17th was badly hit once more, including parachute mines in Pembroke Street and Carnegie Street. At Pembroke Street lorries were again utilised to clear away the debris and although the majority of the casualties were accounted for in two days it was not until 29th that the Rescue Service was able to finally leave the incident. Other serious incidents in the same night were at Stroud Green Road and Foxham Road whilst later in the month a large calibre bomb fell in Poets Road where the Service was responsible for rescuing 3 persons alive and recovering 15 dead.

The night of May 10th 1941 found the Service once again fully extended with what proved to be the last bad night of the “blitz” for Islington. The Rescue Service operated at 9 major incidents including that at Pentonville Prison where one of a string of bombs scored a direct hit on a wing of the prison.

[Read more about Islington and the last night of the Blitz]

The final incidents of this phase of the attack occurred in July when Mildmay Park was hit by several high explosive bombs, resulting in 5 persons being rescued alive and 6 recovered dead.

Respect

Over the whole period, September 1940 to July 1941, the Rescue Service attended at 404 incidents and were responsible for rescuing 479 persons alive and recovering 411 dead. In addition to the rescue work no less than 575 individuals jobs of removal of danger and salvage of furniture were carried out during the same period.

By this time the Rescue Service had by its work at numerous incidents earned the respect and confidence of the general public. By its very nature, however, much of its work remained unobserved and received little publicity. Few realised that the Rescue man often worked alone for hours tunnelling his solitary way through shifting debris and suffocating dust, risking dangerous walls above, the collapse of which might bury him and the trapped casualties he was seeking, and able to hear little but the creak of sagging timber or trickle of slipping debris.

All who were privileged to witness this work at close quarters, however, were struck by the amazing skill, gentleness, and sympathetic considerations displayed to casualties during the rescue operations which seemed to be unexpected from men normally employed in the building industry.

Testimonials: gentle and humane

The following extracts from letters received by the Service bear eloquent testimony to their work:

From a man rescued from the Arsenal Shelter, November 1940

“Two drainpipes being joined together over my head keeping the concrete from crushing me, and the way you men worked to get me out without disturbing those pipes (and saving my life) I shall never forget. May all your efforts be as successful as mine were”.

Camden Road, September 1940

“Not only for the hard work but their sympathy and encouragement”

Brecknock Road, December 1940

“Will you please convey my thanks to the demolition squad who came to the above address…and excavated my dog and buried him in my garden. It was the most gentle and humane piece of work my mother has witnessed…”

Post-raid work

Nor by any means did work end with the recovery of the last casualty, in fact, there was often much hazardous work to perform even at incidents where no trapped casualties had been involved. Buildings seldom collapsed completely and where dangerous walls remained these had to be demolished or shored without the the aid of scaffolding, etc. The work was of a very urgent nature by reason of the fact that the resumption of normal traffic often depended upon its completion to finish quickly to be in readiness to deal with new incidents.

On the lighter side of the Rescue man’s work mention might be made of one case where a lady in night attire who, although reached, at first refused to be removed by him, and of another lady for whom the Service was searching apparently considered that the celebration of her escape was more important than reporting herself to the authorities and who eventually returned to the incident in an advanced state of inebriation.

W. Eric Adams, October 1946

[Original transcript held at Islington Local History Centre. All images Islington Local History Centre, except where stated]

To find out more about people who died during the Blitz, and later raids on Islington and Finsbury, visit the Islington Online Book of Remembrance. You may also leave a personal tribute to all individuals associated with Islington who fell as a result of conflict (1899-1950).

Further reading

- Blitzed Islington: Islington and the London Blitz (1940-1941)

- Islington on the Home Front during the Second World War

- Islington and the Last Night of the Blitz (10/11 May 1941)

- We’ll Meet Again: Islington on the Home Front in Photographs (1939-45) exhibition

- We’ll Meet Again: Islington on the Home Front in Photographs (1939-45) presentation

- Second World War Resources at Islington Local History Centre

Compiled by Mark Aston

Islington Local History Centre | Islington Museum

Islington Heritage Service

September 2020

Leave a comment